Great Sloth Census | The Dog Days Are Over

We don’t know how many sloths there are. We don’t even know how many there should be. And that’s a problem.

Without solid population data, it’s impossible to accurately assess a species’ conservation status. Most sloth species are currently listed as “Least Concern” on the IUCN Red List—but what if that label is wrong?

This photo of Suzi Eszterhas was chosen as one of the top 10 prestigious award for the Wildlife Photography of the Year.

In Costa Rica, we are seeing a different story: sloth populations are declining. In the South Caribbean region alone, sloths make up around 50% of the mammal admissions to wildlife rescue centers - that’s an average of five sloths arriving every single day. That doesn’t sound like “least concern” to us.

How to count sloths

Sloths are secretive, slow-moving, and nearly invisible among the high branches of the rainforest canopy. Counting them is not an easy task. But that’s not unusual in conservation - there are many elusive species that require creative methods to estimate population size.

Thankfully, sloths give us a unique clue: they defecate just once a week, and always at the base of the trees they live in. With that in mind, Dr. Rebecca Cliffe proposed an ambitious idea - to track sloths by tracking their poop.

But there was one big challenge: how do you find sloth poop on the forest floor?

The Great Sloth Census

In 2023, we launched The Great Sloth Census - the first-ever effort to estimate sloth populations using a combination of three methods:

Thermal drones

Trained human observers

A specially trained sloth scat detection dog

To make the third method possible, we partnered with Working Dogs for Conservation to train the world’s first sloth scat detection dog: Keysha, along with her handler, Tamara.

Keysha’s Journey

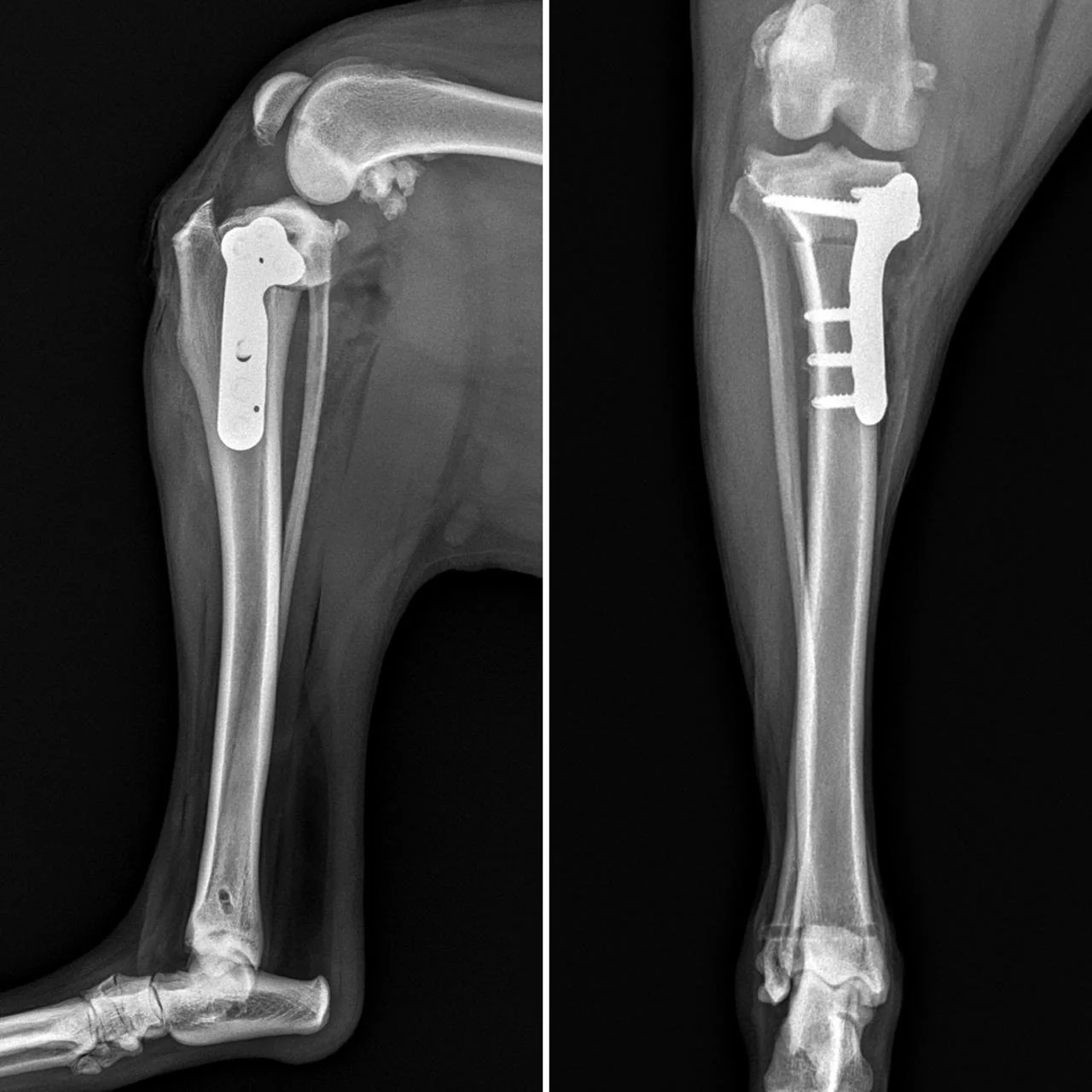

Keysha’s story has been a rollercoaster for everyone involved. After months of training alongside her handler Tamara, their fieldwork hit a series of unexpected hurdles. First, Tamara fractured her foot. Then Keysha suffered a leg injury, followed by a heartworm diagnosis. Just as she recovered, she faced two more setbacks - back-to-back surgeries for torn cruciate ligaments.

In total, Keysha spent seven months out of action in 2024. But she came back stronger than ever.

Thanks to her recovery, we were able to complete sloth censuses at 10 different locations across Costa Rica using all three methods: thermal drones, human observers, and Keysha's scat detection work. This allowed us not only to model sloth populations in the area, but also to compare the effectiveness and efficiency of each detection technique.

Unfortunately, Keysha is now seven years old and approaching retirement. Tamara is also stepping away from fieldwork for now - she's expecting a baby. And so, we must face the fact that the era of Keysha has come to a close.

In early 2025, we began the search for a new detection dog and handler. We trained a young rescued dog named Mila, full of energy and potential - but ultimately, she wasn’t the right fit. Mila’s high prey drive and tendency to become easily distracted made her unsuited to the focused, methodical work needed for scat detection.

A New Chapter in the Sloth Census

While we searched for Keysha’s successor, we began analysing the data already collected through our three detection methods. Together with Anne Kirstine Rosenkvist Kaad from Lund University, we developed spatial suitability maps to identify which methods work best in different habitats.

Here’s what we found:

Human observers detected the most sloths: 0.75 per 0.5 hectares

Thermal drones detected 0.5 per 0.5 hectares - slightly less effective, but far less labor-intensive

Keysha’s scat detection method proved to be the least effective of the three - and when factoring in the financial and time investment, it was also the least efficient.

At first glance, that result may seem disappointing - especially after the effort and innovation poured into Keysha’s training. But in science, an unexpected result is still a result. No one had ever tested the effectiveness of a sloth scat detection dog before. Now, we know.

Moving Forward

After years of trials, challenges, and learning, we are now entering a new phase. Based on the evidence, we have decided to continue the census using the drone and human observation methods.

This is one of the first images we captured of a sloth using our drone!

Now that we know what works best, we are ready to scale up. We will be expanding the Great Sloth Census into new areas and working toward the ultimate goal: a reliable population estimate for wild sloths in Costa Rica (and eventually globally).

Progress has been slow—but then again, sloths have taught us that slow and steady wins the race. And we’re not giving up.