The Legal Sloth Trade And Trafficking

At the recent CITES COP20 summit in December 2025, in Samarcanda, Uzbekistán, the proposal to list both Hoffmann's two-fingered sloth (Choloepus hoffmanni) and Linnaeus's two-fingered sloth (Choloepus didactylus) in CITES Appendix II was adopted, in response to growing concerns about illegal trade driven by the rising demand for selfies and other wildlife attractions.

This is to celebrate!

Recently, the Sloth Institute revealed how the United States has been importing sloths from several Latin American countries with almost no oversight, often for purely commercial use for petting zoos, roadside zoos, and encounters.

These activities have a significant impact on sloth populations even though the species is still classified as "least concern" by the IUCN. Listing them in Appendix II will regulate international trade and offer stronger protection for wild sloths.

What Is CITES and What are Appendices

CITES, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, is an international agreement that regulates or prohibits trade in wild animals and plants to ensure their survival.

Every two or three years, the Conference of the Parties (COP) meets to review progress in species conservation, evaluate proposals to modify the lists of protected species in Appendices I and II, and make key decisions that guide the work of the Convention.

The purpose of CITES is to prevent the unsustainable exploitation of species through international trade. It does this by requiring a permit system for imports and exports, and by placing species into different appendices that define the level of protection they receive.

Species are listed in appendices. They are grouped into three categories based on their conservation needs and the degree of regulation required.

Appendix I: Contains the most endangered species at high risk of extinction. Commercial trade is not allowed. Examples include pangolins, tigers, and gorillas.

Appendix II: Includes species that are not yet threatened but could become so without trade controls. Trade is allowed with permits. This group includes the brown throated sloth Bradypus variegatus, the pygmy sloth Bradypus pygmaeus, and the giant anteater Myrmecophaga tridactyla, a relative of sloths.

Appendix III: Lists species that a country has asked other CITES members to help protect. An example is the northern tamandua Tamandua mexicana, another anteater and relative of sloths.

Sloths Trade, CITES, and the IUCN ‘Least Concern’

Until now, Bradypus variegatus and Bradypus pygmaeus were the only sloth species included in the CITES Appendices. Adding both Choloepus species is an important and long overdue step for sloth protection.

The Proposal 11 to include Choloepus was carried out by authorities and organizations from Brazil, Costa Rica, and Panama.

Except for Bradypus pygmaeus, which is listed by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species as Critically Endangered, the other sloth species mentioned (B. variegatus, Choloepus hoffmanni, and Choloepus didactylus) are categorized as Least Concern.

This means they are not formally considered threatened, but the classification does not reflect the full reality on the ground. Sloth populations are declining rapidly across much of their range, and the countries involved in the proposal consider them threatened.

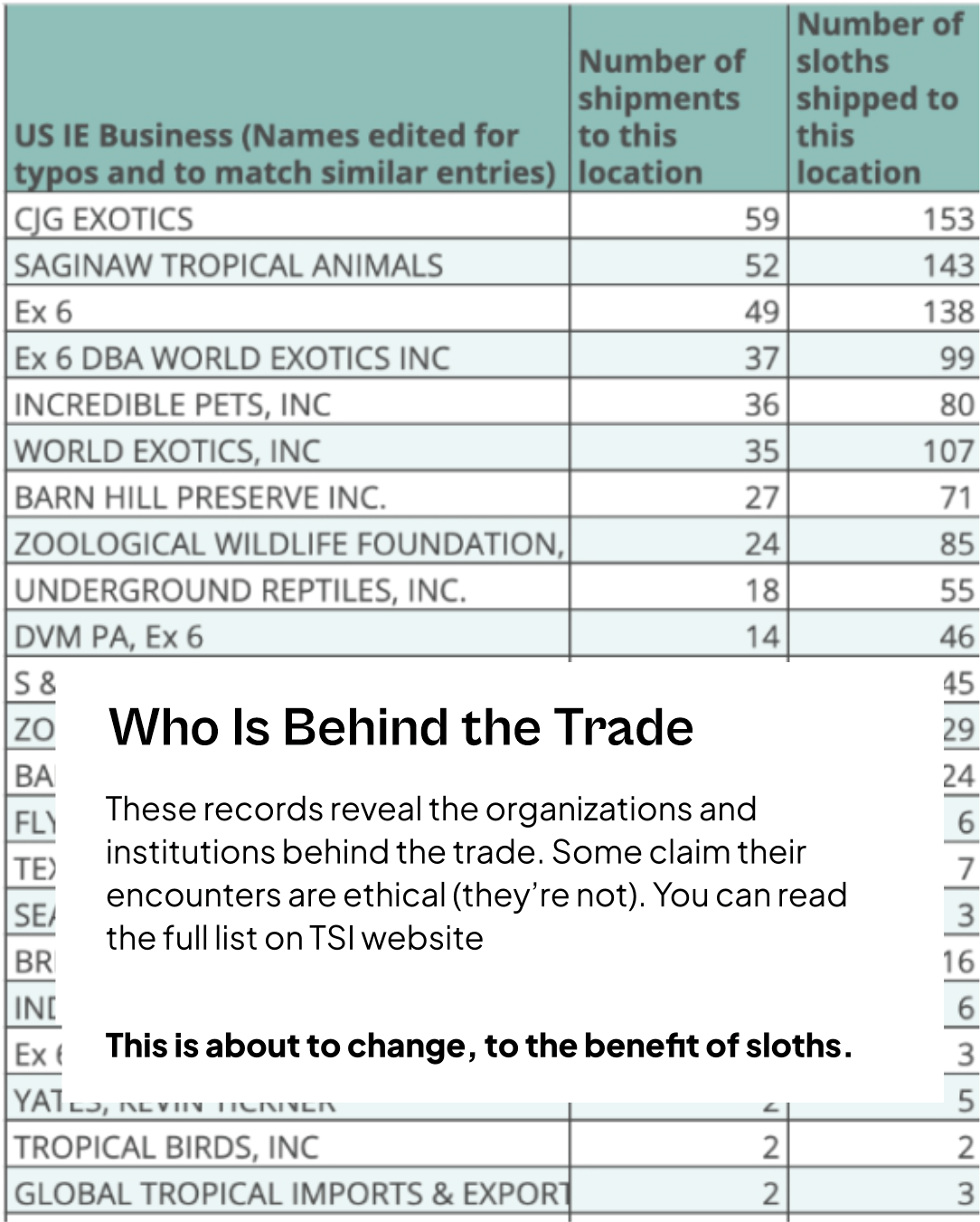

List of zoos importing sloths into the US

Last week, our colleagues at The Sloth Institute released a report based on a decade of federal LEMIS (Law Enforcement Management Information System) data on more than one thousand sloths imported into the United States between 2011 and 2021.

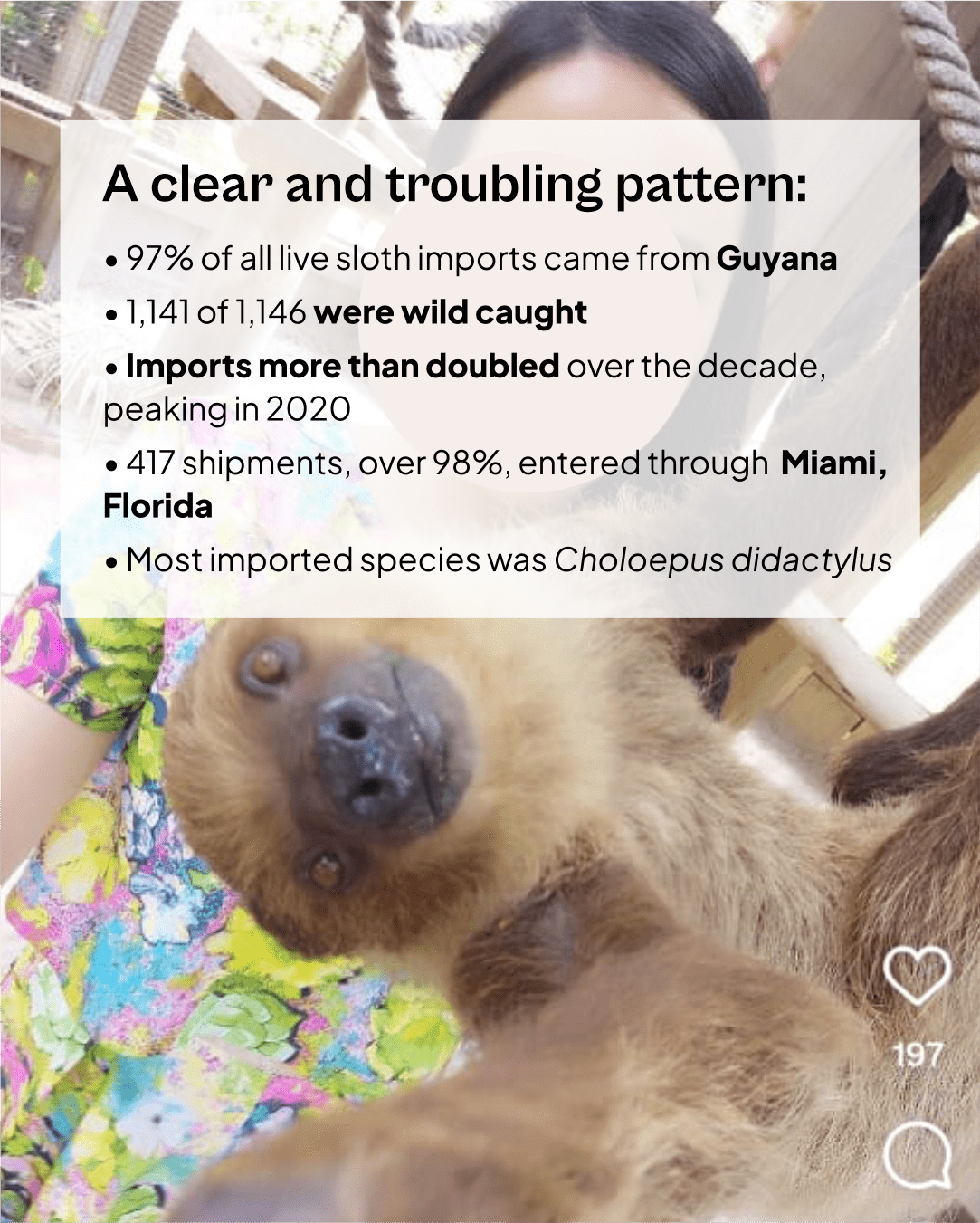

Their key findings show a clear and troubling pattern:

• 97% of all live sloths imported into the US came from Guyana

• 1,141 of 1,146 sloths were taken from the wild

• Imports more than doubled over ten years and peaked in 2020

• 417 shipments, more than 98%, entered through the same port in Miami, Florida

• The most frequently imported species was the two-fingered sloth Choloepus didactylus

With the addition of both Choloepus species to Appendix II, this trade will now be more tightly regulated. Facilities and companies that import sloths for commercial and exploitative purposes will face stronger controls, making this harmful trade far more difficult.

Why are only the two-fingered sloth species traded?

In zoos around the world where sloths are kept, either through trade or captive breeding programs, you will almost always find Choloepus species, the two-fingered sloths. These sloths cope better in captivity compared to the three-fingered species, which require a very specific diet of fresh tropical leaves and are far more sensitive to stress.

Even in specialized rescue centers with trained wildlife veterinarians, caring for three-fingered sloths is extremely challenging. They often experience chronic stress, struggle to adapt, and have low survival rates in confined settings. In simple terms, three-fingered sloths do not survive captivity, which is why the illegal and commercial trade focuses almost entirely on the two-fingered species.

Linnaeus two-fingered sloth (Choloepus didactylus) in captivity

From the jungle to the arms of people

As we see, nearly all live sloth imports are for commercial purposes. Wild caught sloths are supplied to roadside zoos and sloth encounter attractions. Most visitors who pay to hold or hug a sloth for a photo have no idea where these animals come from.

Sloths used as photo props suffer because of stress, poor handling, and a complete mismatch between their natural needs and the conditions imposed on them.

Three-fingered sloths are not safe either

In several sloth range countries, unethical zoos or ‘rescue centers’ still allow visitors to hold three-fingered sloths for photos. Honduras and Peru are among the most problematic ones. As mentioned above, it is not possible to keep Bradypus species healthy in captivity for long periods, and they cannot be bred in these facilities.

This means all sloths used for these encounters come directly from the wild. The heartbreaking reality is that many die from stress after only a few weeks, and are then replaced by newly captured animals.

We can all stop wildlife trafficking and exploitation

We understand why people are drawn to sloths. They are charming animals, and many people on social media tell us they would love to hug one or even keep one as a pet. This usually comes from misinformation, not malice. Once people learn what really happens behind petting zoos and sloth selfies, they usually change their minds and learn to appreciate sloths from a respectful distance.

Legislation is essential to regulate and reduce this trade, but demand also needs to stop. Without customers, there is no market.

Education and awareness may feel slow, but they are a crucial part of ending wildlife exploitation in tourism, entertainment, and social media content.